Where did all the love go? Feelings in the novel.

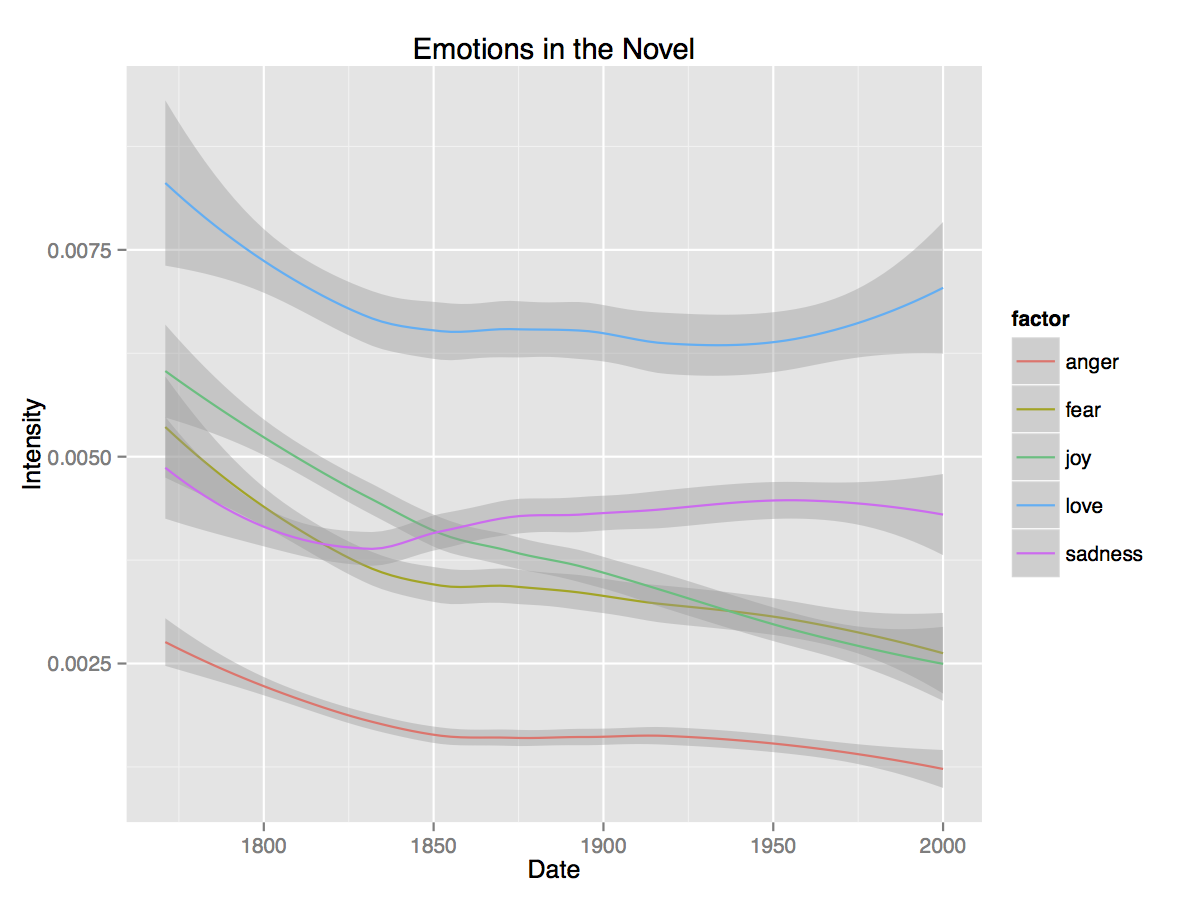

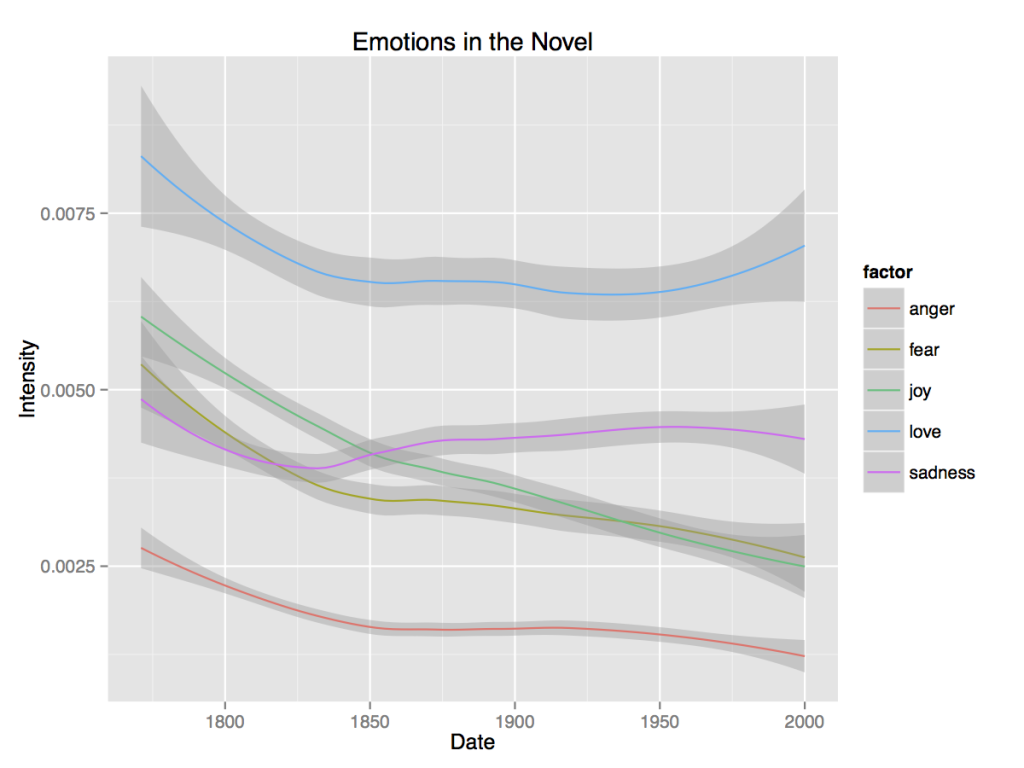

I have been increasingly focusing on the history of feeling in the novel, especially as a way of differentiating feeling from sentiment analysis. Emotions aren’t the same as sentiments, as they are commonly defined today (and usually only in binary fashion — happy/unhappy or positive/negative). Instead, I was interested in the ways different kinds of emotions change as the novel evolves and what kinds of configurations one might find — the way words for sadness move and reposition in relation to words for joy or love or even anger.

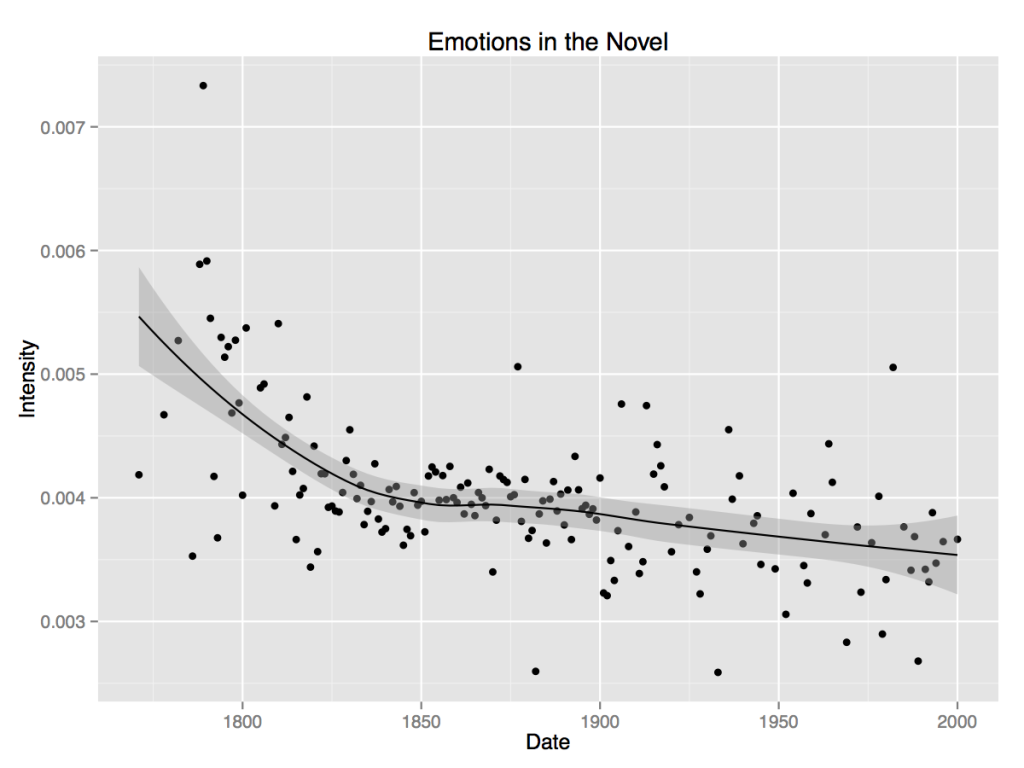

I’m still working on this, but I did want to share an interesting insight about the overall decline of emotionality in the novel. While I know we associate Romanticism with the pathetic and the bathetic, I was still surprised at how much the vocabulary of emotions declined as a percentage of words within the novel overall. We have indeed gotten colder — at least the list of canonical novels has.

Things really fall off the charts if you compare contemporary novels with the novel of the long nineteenth century. These are novels published between 2012-2014 and reviewed in the NY Times Book Review — suggesting that they have some kind of highbrow (but not too high) identity. Here are the different averages for all emotions in the novel:

19C Novel = 0.015117854

Contemporary Novel = 0.008936122

Look again at those numbers. The first one isn’t twice as much. It’s 17x as much. The contemporary novel is seventeen times less defined by a vocabulary of feelings than its predecessors of the long nineteenth century (1770-1930). That’s insane (and usually grounds for suspecting the data is off, but I keep checking it…Keep in mind too that the words are coming from a contemporary thesaurus). The Young Adult novel interestingly gets closer (avg = 0.01030404), suggesting an answer as to where the novel’s feelings are hiding these days.

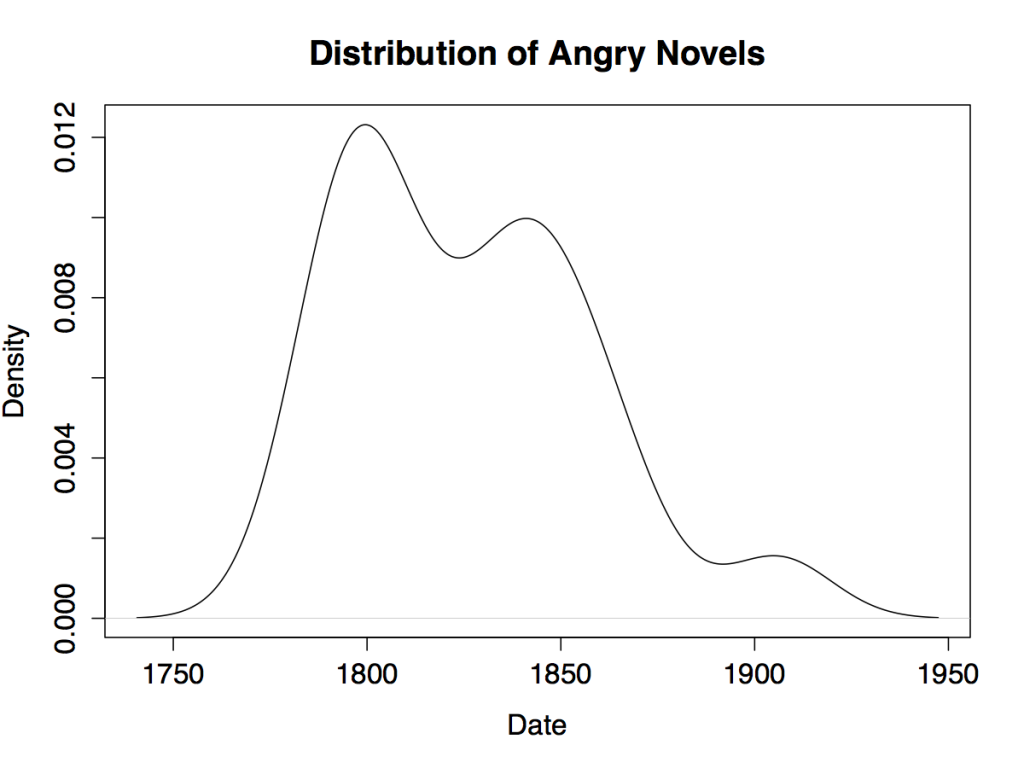

Last, for the Romanticists out there, I was intrigued by the centrality of anger to the Romantic period, where most of the highest scoring angry novels are located during this period. So things Romantic are not just more emotional, but also more volatile, fitting for a period of revolutionary and post-revolutionary unrest.

I’m still wondering where all those feelings went for the adults?