An Open Letter to the MLA

Dear Prof. Taylor,

I am writing to you as a member of the MLA who has concerns about the practices and policies relating to the society’s data and its impact on research. This is an issue that effects many scholarly organizations. For this reason I have chosen to write an open letter.

The MLA has emerged as an important champion of the principles of open access scholarship. The creation of the MLA Commons represents a recent positive example of such pro-active work.

It is all the more troubling to realize that such open access does not apply to the MLA’s own data. I was recently served with a take-down notice by my university library for publicly sharing data and code used in a recent publication with the PMLA. The data was drawn from the MLA database and represented two years worth of records, one collection from 2015 and one from 1970. When I contacted the MLA to ask for the data outside of such corporate mediation I was refused. Here we have a case where data from the MLA was used to support an article published by the flagship publication of the MLA that is now being repressed from public view.

The MLA database is an essential source of knowledge about the practices within our field. As we have begun to learn, metadata alone can reveal a great deal of information about the behaviour of a community. In my own work I am interested in studying the concentration of attention surrounding literary authors, especially with respect to gender and racial diversity and how such concentration has changed (or not) over time.

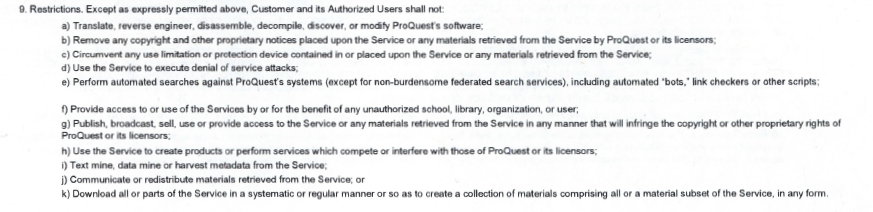

Below I attach a screenshot of the licensing agreement that my university has signed with ProQuest, who distributes the data for the MLA to our university library. As you can see, principles i-k all violate essential norms of research. Not being able to mine a database (i) means that it has been walled off from standard research practices. Not being able to communicate materials received from the service (j) means that the evidentiary bases of claims using the data cannot be publicly shared or externally validated. And not being able to download parts of the service in a systematic manner (k) means that we cannot study the contents of the database in any responsible fashion. These are all principles that favour a mode of interaction with information that is both out of date and prohibitive in terms of the accepted norms of academic research today.

The MLA, and it should be added numerous other scholarly organizations, have contracted out the organization and access to their data to third parties, most of whom are private, for-profit initiatives. These parties’ business models are in direct conflict with the scholarly mission of the society, indeed any academic society. While this may have been an arrangement that was initially convenient, not to mention profitable, it is no longer an acceptable way of curating data within an academic context. Libraries need to stop signing license agreements that limit access to data in the library. And scholarly organizations need to stop signing license agreements that limit access and the public circulation of their data. Anything short represents a serious abrogation of scholarly responsibility.

I would be happy to work with you to craft data policies that are more in line with the values and norms of scholarship. The MLA has an opportunity once again to take the lead in this important matter.

Sincerely,

Andrew Piper