Novel Worlds: Theory + Computation

I am very excited for our *fifth* (!) annual NovelTM conference coming up this week. The aim of this year’s conference is to begin the long overdue conversation between data-driven research and literary scholarship more generally.

The particular theme of the conference will centre around the question of “worlds”: How are we to think about the worlds of the novel, either the possible worlds constructed by novels or the worlds of readers outside of the novel that novels help shape? One of the reasons that I think this topic is particularly appropriate is because it draws attention to how important modelling is — both to the novel and to computational research.

In her wonderful novel Station Eleven, the Canadian writer Hilary St. John Mandel imagines a world in which more than 99% of humans have died due to a dangerous flu. The world essentially starts over, with no electricity, no internet, no internal combustion engines. That is to say, when it starts over, it also shrinks dramatically. No one knows anything about worlds beyond their immediate world. Your knowledge extends as far as your feet. At the same time, memory of the prior world plays an important role in motivating characters’ actions and also in drawing together different elements of the plot. People are connected through the past, one that is rapidly withdrawing from the lived experience of characters as time marches forward. The world gets much bigger and much smaller at the same time.

I think Station Eleven is a useful example to frame the conference because it is explicitly about the beginnings, ends, and boundaries of worlds, both individual and global, both spatial and temporal. It highlights the way fiction in particular, and its most dominant modern incarnation, the novel, is fundamentally invested in imagining possible or alternative worlds that exist and transverse both time and space. The novel models. It simultaneously makes claims to completeness — it accounts for its fictional universe as a totality, as coherent and extensive (everyone in Station Eleven is acting according to the rules of Station Eleven) — just as it also makes claims to its partiality, to the perspectival and contingent nature of its world-making. We only know what we know through the vantage point of specific characters. We never have the “full picture” (or “world picture” in Heidegger’s terms). It asks us what it means to live a life and make judgments without complete knowledge of what’s going on. It is an experience of partiality and completeness at the same time.

Why am I making so much of this modeling or potentiality of this novel, or the novel? Because I think novels are an amazing cultural technology for allowing us to engage in model thinking, to think in models — to imagine the world hypothetically, to test it, to rotate it, to acknowledge incompleteness amidst the desire for coherence and wholeness. I think this is one of the great affordances of novels as a genre.

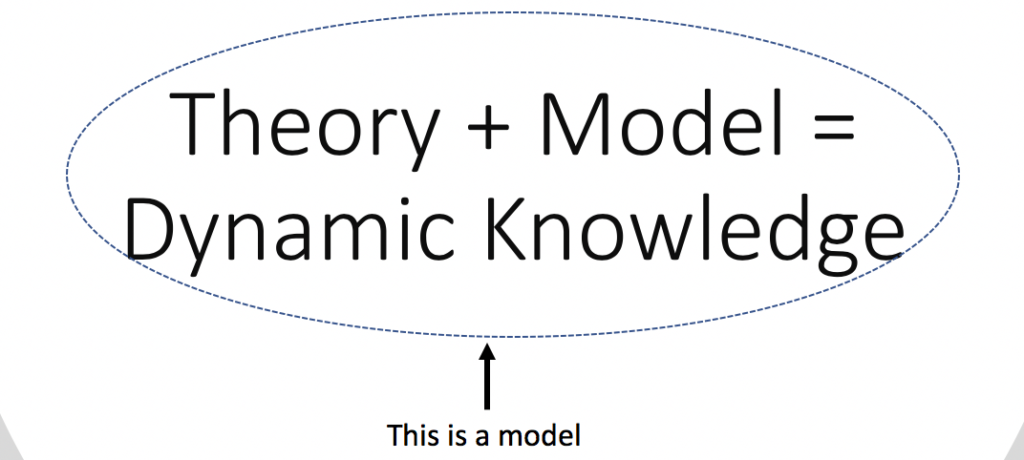

All this model talk that belongs to the idea of worlds, and novel worlds in particular, is a useful way to also think about the subtitle of the conference: “theory + computation.” This isn’t just a convenient roping together of two otherwise incompatible things. Rather, it is an argument for their programmatic relationship. If nothing else, this is what I want us and the field to take away from an event like this. A theory without a model is inert: without some way of testing it it can’t do anything. But a model without a theory is potentially even worse: it has no idea what it’s doing.

So the hypothesis I want us to test at this conference is that the combined practice of qualitative theory-building plus computational model-building creates a form of dynamic knowledge that is far better than either practice alone. Neither mode alone has access to the truth, but the two together make for a more dynamic intellectual field. To model it: