Buying the news

We have a new piece out in the journal, New Media and Society, by lead author and lab student, Benjamin LeBrun, on the effects of hedge fund ownership on local news coverage.

We were inspired to start this project by a piece that appeared back in 2019 that highlighted how a number of publications have become “zombies” after being purchased by corporate hedge funds, a process which the authors colourfully called “The Mavening.” A mavened publication is one that continues to exist in name, but whose purpose — and staff — have largely been downsized. From Deadspin to Sports Illustrated to The Denver Post, the authors lighlighted a list of illustrious publications whose newsrooms and missions have been drastically cut back. As they write, “The Mavening is the way media overlords taunt readers by forcing them to watch as they drag around the corpse of a beloved friend.”

At the same, a variety of concerns have been raised about the loss of local news coverage through corporate consolidation. As the news ecosystem is deprofessionalized and delocalized critics have serious concerns about the quality and relevance of information for communities.

We jumped in and decided to see what effects such ownership events had on local news coverage providing the first ever estimates of effects of ownership on local news coverage.

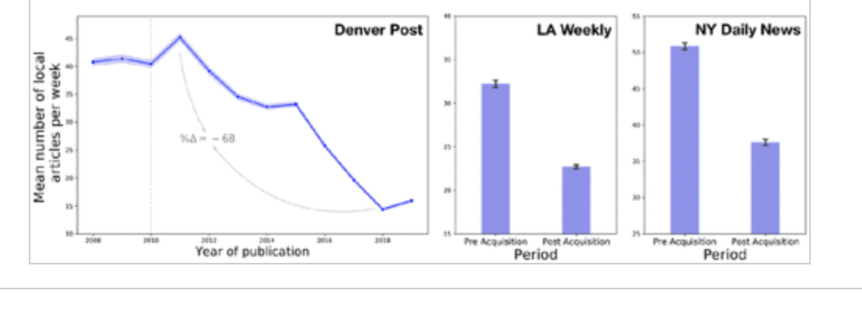

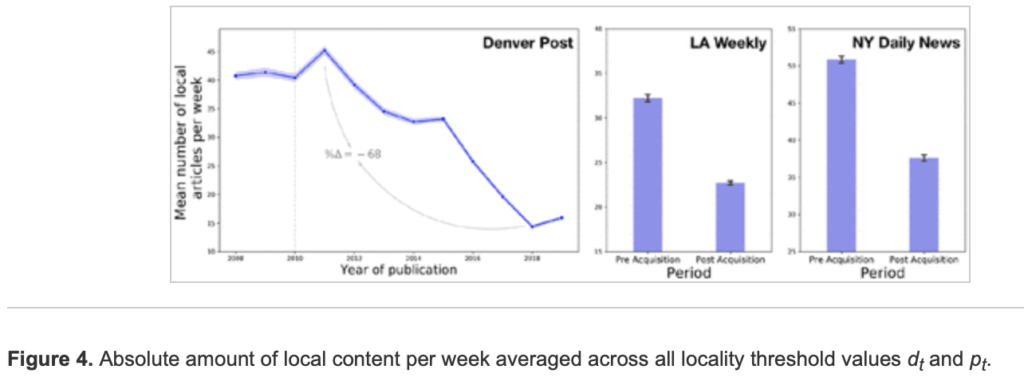

We focused on two different kinds of acquisition events: corporate acquisitions, when a corporation purchases a high profile local paper. These papers included The Denver Post, LA Weekly, and the New York Daily News. The second, corporate consolidation, looked at a collection of 28 publications purchased by Digital First Media, that engaged in high levels of article sharing among sister publications. In all we survey 31 publications and over 130,000 news articles over the past two decades.

As we discuss in the paper, we find:

- Acquisition leads to a significant, but not disproportional, decrease in the volume of local content produced by local newspapers;

- Coverage of local places in the periods following acquisition is significantly more concentrated than coverage in the periods prior to acquisition;

- Articles produced to be shared across regional hubs of newspapers are significantly less local—and discursively more national—than articles unique to a given newspaper.

Here is one of the main figures in the piece:

One of the most interesting things about working on this project was how to detect local news. Ben came up with some really interesting solutions described in the paper. The short version is that we not only had to identify the locations mentioned in articles but also come up with a way of defining “locality” that was both relative in terms of distance (when is an article not “local”) and relative in terms of proportionality (how many mentions of local places make an article “local”). Ben’s formalization of this problem looked like this:

An article is considered local if pt proportion of the toponyms mentioned in the article are within dt distance from the center of the city the article’s publication purports to cover.

For instance, setting dt = 50 and pt = .75, this definition states that an article is local if at least three quarters of its toponyms are within 50 km from the center of the publication’s city. We compute, for a given set of articles, the number of local articles by averaging over all possible definitions of locality, that is, all (pt, dt) ϵ {0.05, 0.1, . . ., 1} × {20, 25, . . . 50}, where × denotes the cartesian product operation.

We also measure local coverage as “people” by looking at mentions of local politicians and municipal figures for the Denver Post. Finally we try to measure “national discourse” by comparing our papers to aggregate vocabulary distributions of national news outlets like CNN and FoxNews.

All told a great project that shows the power of Cultural Analytics to provide empirical foundations for policy discussions regarding the media.