World Authorship: Three Computational Frameworks

The following is a condensed version of a talk I delivered recently at Lancaster University in the UK as part of the research project on “Authors and the World.”

Both “world” and “authorship” are complex terms that have, on the one hand, very straightforward meanings – the world is coincident with everything on the globe or earth, authorship defines documents written by people – but on the other hand contain a range of more complicated aspects that we know need a good deal of unpacking – at what point is something or someone “worldly”? When should we use the term global instead (what is the difference between global and worldly?). On the authorship side, How can we be certain a document belongs to a person? Or how might we represent the document-person diad as a single, unchanging entity? The point I want to make today is that if we are going to be talking about these two things, world and authorship, then I think at least part of our approach has to be computational. We need a method to match both the scale and the nature of our claims.

In this regard, the work of Michel Foucault still strikes me as a relevant framework through which to imagine computational approaches to thinking about world authorship. For Foucault, an “author” was first and foremost a juridical concept, a punishable object. It was in this sense a category largely constituted by what we today would call metadata: the number of copies, books, translations, and reprints that an author produced and that could be attached to a proper name for legal purposes of both accounting and being accountable. In this case, the UNESCO Translation Index offers a potentially rich resource for mapping such international circulations of authors. It can allow us to chart the reach of different authors through translation at different points in time.

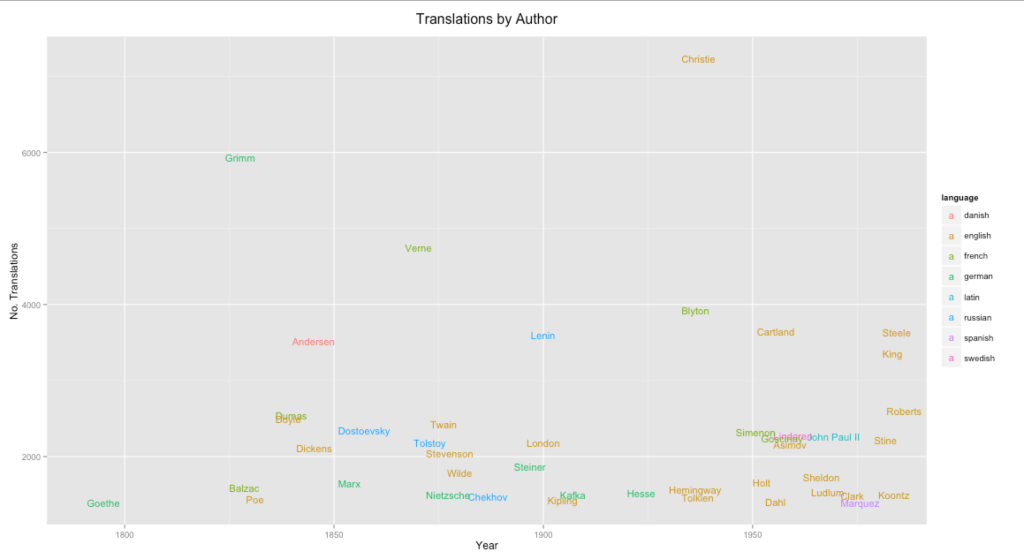

Below is a graph of the total number of translations published since 1980 plotted according to the mean of authors’ birth and death dates. It allows us to see a few salient details about the recent past of translation:

- almost all of the most translated authors were active in the nineteenth century or later (with the exception of Shakespeare, Plato, Perreault, and Rajanisa).

- children’s literature is a very strong component of translation (the Grimms, Anderson, Blyton, Tolkien, and Dahl).

- and the gradual emergence of global English also comes through, as many of the most recent most translated authors are largely in English (orange).

The second way an author was understood by Foucault was more complexly as a kind of ideological construct – a projected unity that served different kinds of disciplinary as well as psychological ends. “Goethe” is the person to whom I ascribe some kind of formal or conceptual coherence – the inventor of the Bildungsroman, a poet of nature, theorist of morphology. When I invoke this name, I do so to engage in some form of casuistry, to convince you about a belief I have. The proper name, in this regard, serves as an effective ideological medium.

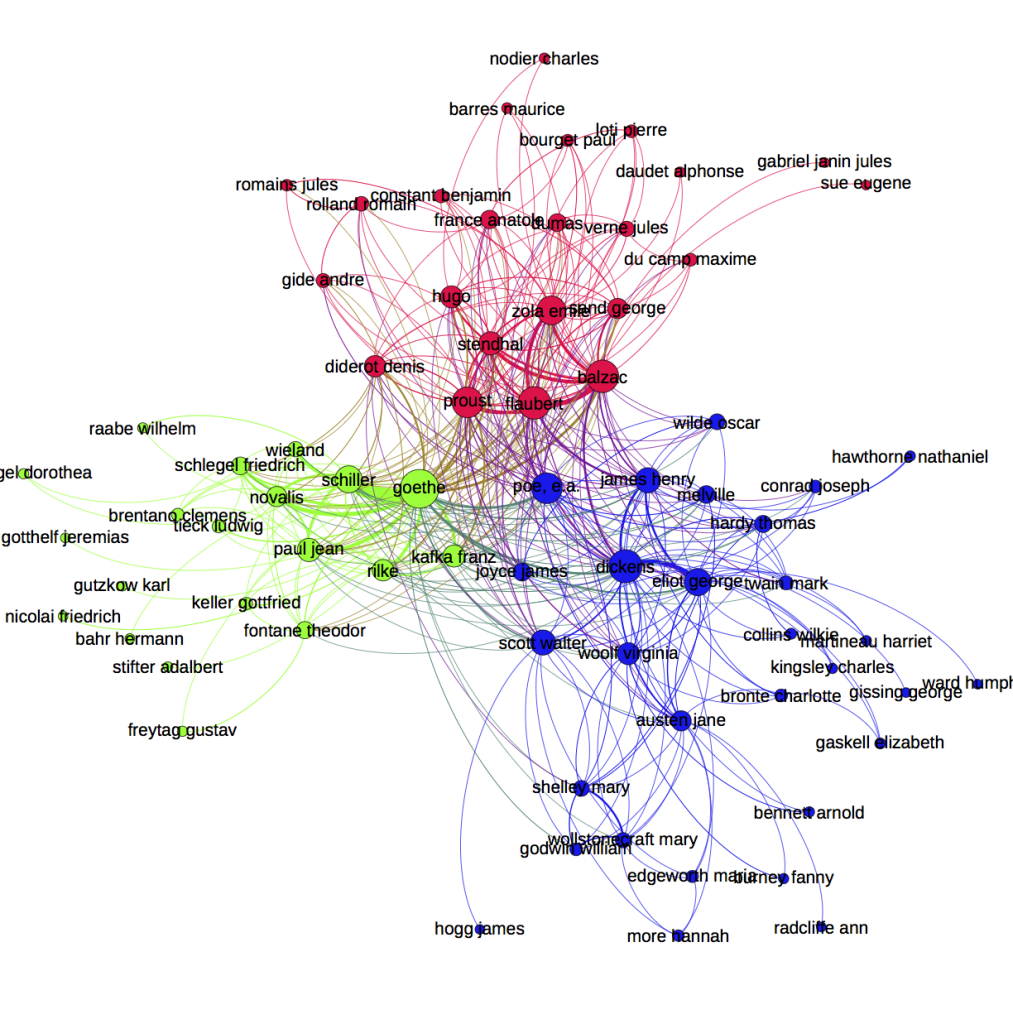

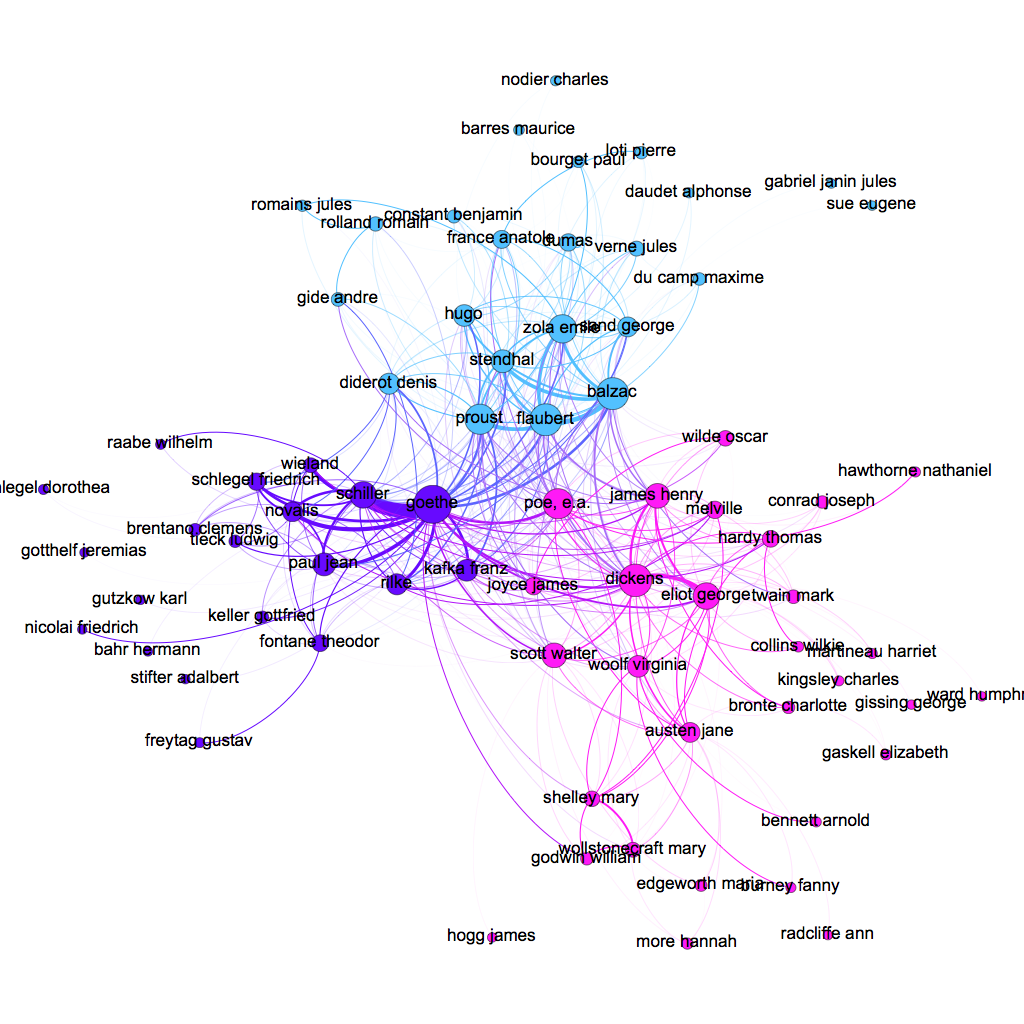

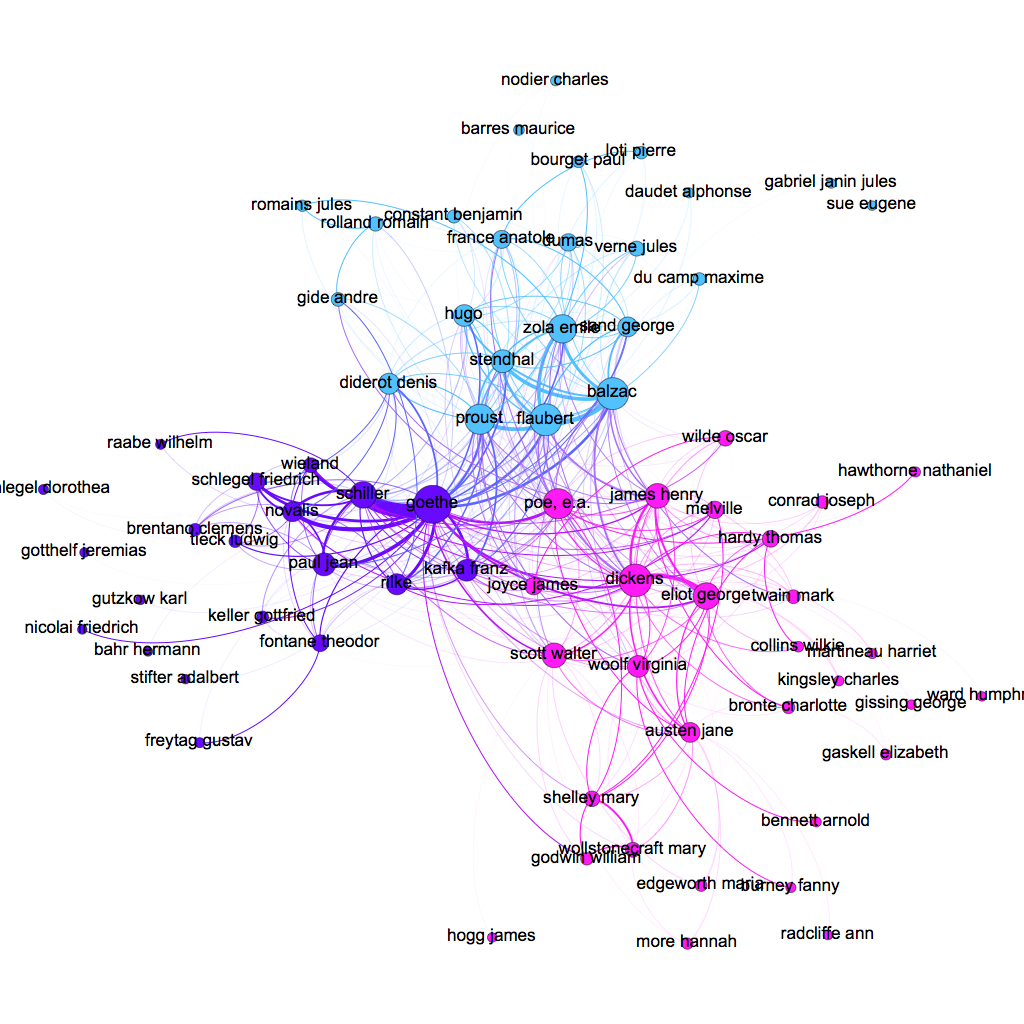

This too we can try to measure. I am currently at work on a larger project on authorship, language, and the failures of comparative literature, and what you see below is a graph detailing the co-occurrence of author names in a set of 30,000 JSTOR articles drawn from the field of languages and literatures. The first network is coloured according to languages and the second according to a community detection algorithm. As you can see, they are perfectly identical with one another. The author, according to these results, has served as a potent tool of nationalism, of the orientation of literary scholarship around monolithic language communities. The “author function,” from this point of view, is equivalent with a “nation-function.”

Finally, Foucault’s third idea was that an author is an initiator of discourse, a reference point not for the understanding of generic similarity – Radcliffe gives birth to a bunch of novels that all resemble hers – but the production of new kinds of conceptual differentiation. The Unconscious as a discourse, to take Foucault’s most famous example, does not consist exclusively of simply Freudian terms, but a variety of new ways of thinking about human being and cultural production. Authorship in this third sense, then, is the combination of a linguistic signature and its aftermath, the actions that it performs not on a subsequent textual field, but the ways in which it makes a subsequent textual field appear as a field.

This is the work that I have been undertaking in my project on The Werther Effect, which I won’t go into here. But the aim of the project is to understand how an authorial signature allows for new kinds of discursive communities to emerge and to identify what the concerns of those communities are.

1 Comment

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

[…] nineteenth century. That’s actually not as arbitrary a time period as it may sound — as I’ve shown elsewhere, if we look at world translations the nineteenth-century marks the cut-off of still widely […]