Modelling Plot: On the “conversional novel”

I am pleased to announce the acceptance of a new piece that will be appearing soon in New Literary History. In it, I explore techniques for identifying narratives of conversion in the modern novel in German, French and English. A great deal of new work has been circulating recently that addresses the question of plot structures within different genres and how we might or might not be able to model these computationally. My hope is that this piece offers a compelling new way of computationally studying different plot types and understanding their meaning within different genres.

Looking over recent work, in addition to Ben Schmidt’s original post examining plot “arcs” in TV shows using PCA, there have been posts by Ted Underwood and Matthew Jockers looking at novels, as well as a new piece in LLC that tries to identify plot units in fairy tales using the tools of natural language processing (frame nets and identity extraction). In this vein, my work offers an attempt to think about a single plot “type” (narrative conversion) and its role in the development of the novel over the long nineteenth century. How might we develop models that register the novel’s relationship to the narration of profound change, and how might such narratives be indicative of readerly investment? Is there something intrinsic, I have been asking myself, to the way novels ask us to commit to them? If so, does this have something to do with larger linguistic currents within them – not just a single line, passage, or character, or even something like “style” – but the way a greater shift of language over the course of the novel can be generative of affective states such as allegiance, belief or conviction? Can linguistic change, in other words, serve as an efficacious vehicle of readerly devotion?

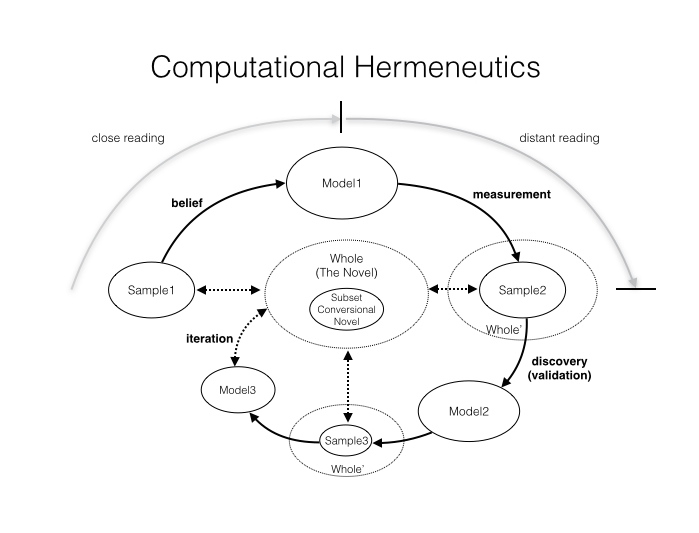

While the full paper is available here, I wanted to post a distilled version of what I see as its primary findings. It’s a long essay that not only tries to experiment with the project of modelling plot, but also reflects on the process of model building itself and its place within critical reading practices. In many ways, its a polemic against the unfortunate binariness that surrounds debates in our field right now (distant/close, surface/depth etc.). Instead, I want us to see how computational modelling is in many ways conversional in nature, if by that we understand it as a circular process of gradually approaching some imaginary, yet never attainable centre, one that oscillates between both quantitative and qualitative stances (distant and close practices of reading).

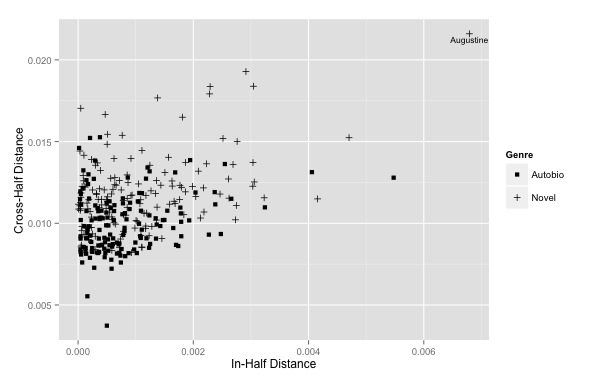

My approach consisted of creating measures that tried to identify the degree of lexical binariness within a given text across two different, yet related dimensions. Drawing on the archetype of narrative conversion in Augustine’s Confessions, my belief was that “conversion” was something performed through lexical change — profound personal transformation required new ways of speaking. So my first measure looks at the degree of difference between the language of the first and second halves of a text and the second looks at the relative difference within those halves to each other (how much more heterogenous one half is than another). As I show, this does very well at accounting for Augustine’s source text and it interestingly also highlights the ways in which novels appear to be far more binarily structured than autobiographies over the same time period. Counter to my initial assumptions, the ostensibly true narrative of a life exhibits a greater degree of narrative continuity than its fictional counterpart (even when we take into account factors such as point of view, length, time period, and gender).

CrossHalf

Novel Mean 0.013847732

Autobiography Mean 0.009992367

p-value (t.test) 2.2e-16

p-value (wilcoxon) 2.2e-16InHalf

Novel Mean 0.001141110

Autobiography Mean 0.000797757

p-value (t.test) 4.03e-05

p-value (wilcoxon) 0.0003017

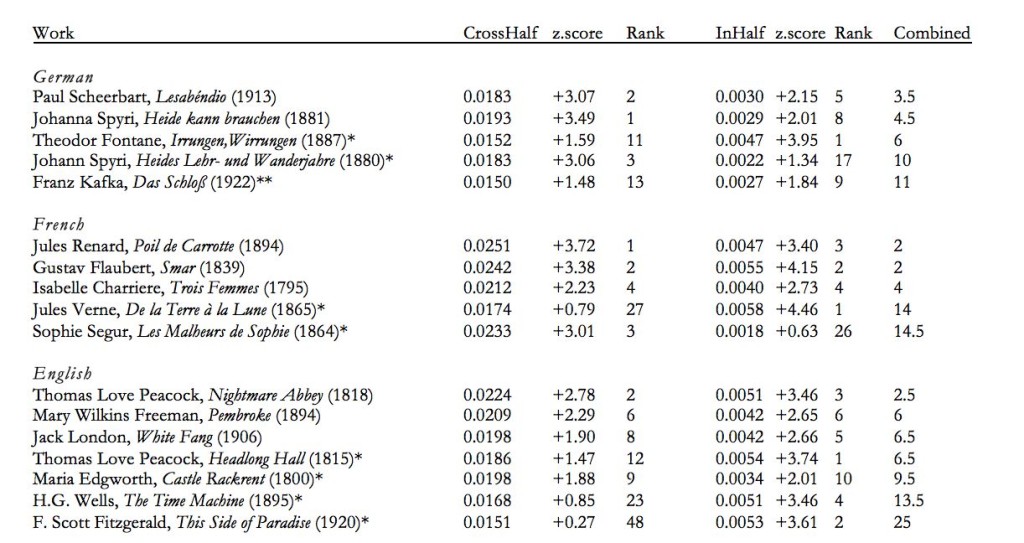

The second interesting finding is part of what I call the validation-discovery section of the paper. Assuming that there is a greater degree of “change” within novels, what are those novels about that exhibit abnormally high degrees of such change? Do they have anything to do with “conversion”? Below is a list of those novels that have significantly high conversion scores, which leaves us with something of an interesting literary historical riddle: what do Heidi, Lesabéndio, White Fang, Impey Barbicane, Barnabas Thayer, Poil de Carrotte, and Kafka’s K. all have in common?

As I show in the paper, what is interesting about these novels is the way each is marked by a high degree of binariness, but the way such schismatic plotting is used for different ends. In some cases, as in the Heidi novels, the point is literal conversion — the Grandfather at the novel’s end is converted to Christianity and of course the Book. In Jack London’s White Fang, conversion isn’t religious, but social in nature — coming in from the Wild. In other cases, as in science fiction novels, the point is planetary escape — to experience a highly transformative spatial rupture, one that poses fundamental communicative quandaries, as in Jules Verne’s De la Terre à la Lune. How can you communicate this new state to the planetary remainder? Finally, in the double marriage plot, we see how a strong degree of binariness is used to generate social order — the realignment of a misaligned quadrant into its respective halves. This can either take the form of resolution, as in Mary Freeman’s Pembroke, or one of constriction and loss, as in Fontane’s Irrungen, Wirrungen.

Beyond the individual cases, the main point is the way this method is linguistically neutral in its assumptions about conversion — it does not start with a given vocabulary of conversion (though I looked at that too), but rather looks only at the relationships between words within a given text. Such linguistic neutrality allows for the capturing of different kinds of conversional experience, but ones that nevertheless share certain structural properties. It allows us to see the continuities of difference that I think is computational reading’s hallmark.

As you’ll see in the piece, I offer 5 hypotheses on how to further measure this notion of conversionality in the novel. The validation of the model (close reading) is not an end in itself. Rather, it is the beginning of further testing (distant reading). By way of conclusion, I post these here:

Hypothesis 1: Conversional novels are defined by nature/culture dichotomies, where nature is a proxy for the divine. Create dictionaries based on these novels (consisting of words for “culture,” such as civilization, justice, reading etc. on the one hand, and words for “nature,” i.e. alps, trees, wilderness, etc., on the other) and measure their intensities. The stronger both vocabularies are, the more conversional a novel can be said to be.

Hypothesis 2: Conversional novels are defined by a topos of incommunicability. Create measures of phrases that articulate a communicative impasse such as: a) subjunctive phrases like “als wäre” or “as though + verb”; or b) said + negation (“said nothing,” “did not say,” “could not say” etc.). Higher conditionality and higher negativity should correlate with greater conversionality and its incommunicability.

Hypothesis 3a: Conversional novels are structured by strong binary geographies, which are marked by different ways of speaking. Using named entity recognition do we find the grouping of names into different lexical communities? The stronger the dichotomy between them (the clearer their difference), the more conversional a novel could be said to be.

Hypothesis 3b: Conversional novels are marked by an increase in polysemy over the course of the novel. Lexical reduction corresponds to semantic complexity. Could we create a measure that accounts for the semantic ambiguity of a text, the ways in which it becomes increasingly difficult to locate a word’s particular meaning? Implement a series of tools – part of speech tagging, machine translation – and see the degree to which they fail. Ambiguity should correlate with greater difficulty of automation and these values should subsequently increase as the novel progresses.

Hypothesis 4: Conversional novels are recursive. They recapitulate themselves as they progress, slowing themselves down as they expand internally. This is devotion as a form of imbrication (we cannot get out). Diegetic levels – narration within narration – should therefore increase over the course of the novel. There is also an aspect of social network analysis to this – the introduction of new characters retards rather than furthers narrative progression. Is there a correlation between the growth of characters, the growth of intra-diegetic narration, and the slowing down of plot?

1 Comment

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

[…] Building modelshttps://txtlab.org/2015/01/modelling-plot-on-the-conversional-novel/ […]