Does the decline of gender within literary studies matter?

A little while back I posted on the unmoving ratio between male/female pronouns in a data set of ~60,000 articles in literary studies. The ratio has been stable at about 2:1 since the mid-1990s. While pronouns do not tell us everything we need to know about the distribution of gender in research, for a field that is highly people-centric they certainly tell us a lot.

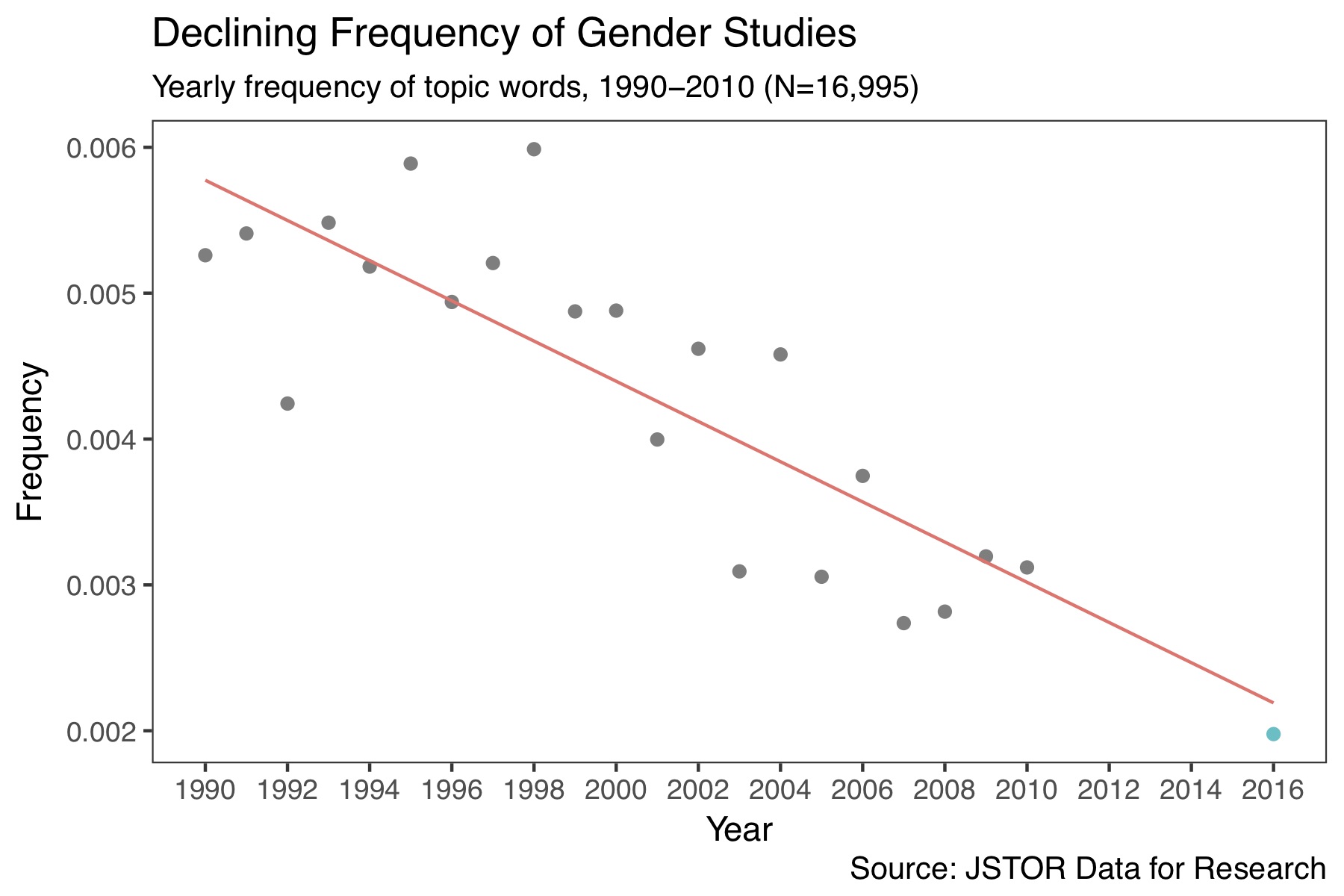

Since then I’ve been working with more models to understand how gender has played out as a category of research in the past half-century. The figure below shows the rise and fall of the “gender studies topic”, which was derived using LDA with 60 topics. As I mention elsewhere, it is one of the most stable topics across multiple runs and multiple topic-size parameters.

I have a bunch of further tests that help show how this decline isn’t really diffusion — the idea that gender just gets so normalized in the field it no longer holds together as a distinctive “topic.” But what I wanted to show today was another insight that I discovered when I was concerned that my data stops in 2010. Maybe, I asked myself, maybe things tick back up. Maybe this decline is just temporary.

Or maybe not. As far as I can tell with a smaller sample we put together of nine major journals (see list below), things look exactly as we would expect, which is to say, worse.

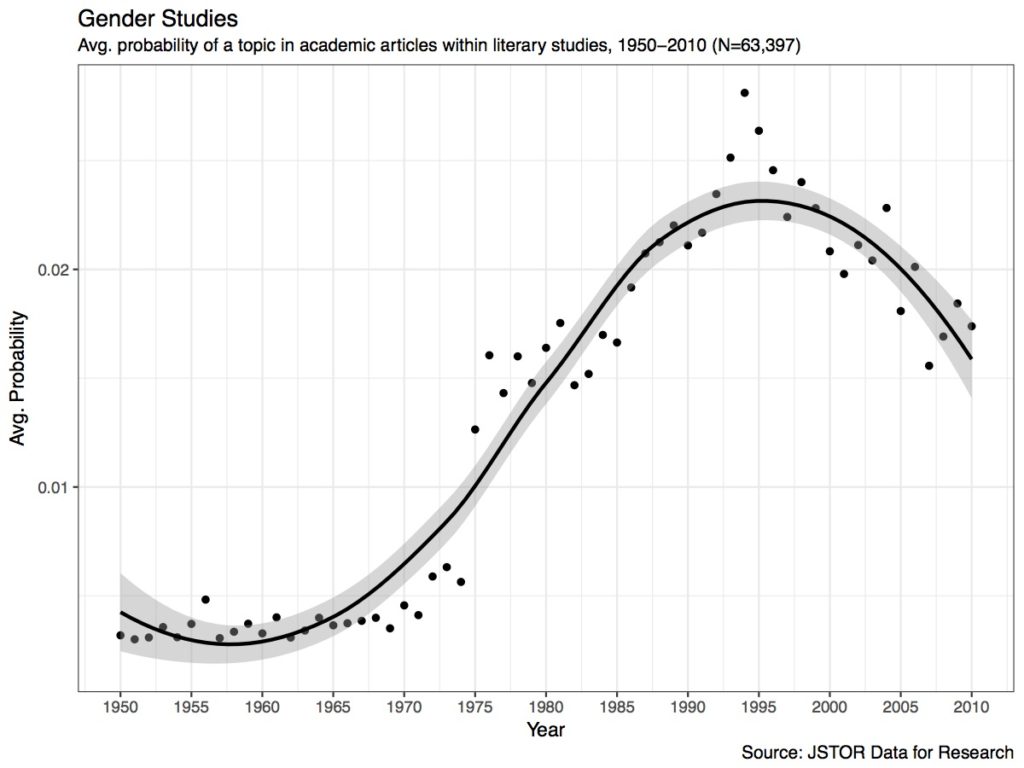

What you see here are the frequencies of the top 10 words from the gender studies topic (see word list below) as they appear in our mini-sample of nine journals since 1990. The JSTOR data cuts-off in 2010 and we scraped just one year in 2016 for comparison, which is why there is a gap between 2010 and 2016. Given the trend, and assuming it’s linear, we would estimate that the rate of these words combined frequency should be about 0.0022 in 2016 (where the red line ends). That would be down more than 60% from the mid-90s peak.

What we actually see is the blue dot, a rate of 0.0020, or just about what we expected.

I have to say this completely surprised me. That the rate of talking about gender would be predictably linear over the past six or even 25 years is a little creepy. It’s not quite as neat as colons in titles, but still.

Of course, this is just nine journals and one year. You would see differences if you sampled differently or took a five-year average. But even if you adjust these words’ level of occurrence — even if you double them — the rate would still be strikingly low compared to its pre-2000 highs. Or maybe this set of words is just not cutting it. Maybe it’s a bad set. And yet it isn’t clear to me how you would talk about gender without gendered language so I’m not sure how else you might model this.

In other words, it seems to be the case that in a sample of mainstream journals we in literary studies are talking about gender in less explicit ways than we did in the past and that this trend has continued in a very predictable way. Some might say it’s high time to give up on the explicit study of gender. Let’s just talk about literature and give up on questions of identity.

But as we saw with the pronoun data, when we give up on talking about gender, we just leave inequality in place.

***

Here is a list of the journals we used for this test:

sub.sample<-c(“Studies in Romanticism”, “Studies in the Novel”, “PMLA”,

“New Literary History”, “MLN”, “The Modern Language Journal”,

“The Modern Language Review”,”ELH”, “Critical Inquiry”)

Here is a list of the topic gender studies topic words:

w<-c(“women”, “female”, “woman”, “male”, “womens”, “men”, “gender”, “feminist”, “sexual”, “sex”)