Are academics more unequal than athletics? A new collaboration by Brian Powell

Our latest lab collaboration was created by McGill undergraduate Brian Powell. As a college basketball fan, he was interested in whether the high levels of institutional inequality within academic publishing and hiring that we have been seeing would also hold true within college athletics. Did sports exhibit similar levels of elitism as intellectual work?

After collecting data on 1,742 players drafted into the NBA since 1989, Brian found that the distribution of institutions across players drafted was considerably more equal for college basketball than our academic publishing study. As Brian reports, the Gini co-efficient for players drafted into the NBA is 0.594 while for academics to be published in elite humanities journals it is 0.785. There is a much stronger skew towards favouring a small number of schools when it comes to who gets published in top journals than there is in who gets into the NBA.

I’m not sure what your reaction is, but I was pretty shocked. My assumption was that pro sports is about as selective as any system can be and that given the small size of NBA teams that a very few college power-houses would be feeders to becoming a professional. While certainly concentrated, it comes nowhere near levels we see in academic publishing. This deserves some further reflection. We’re more exclusive than the NBA!!

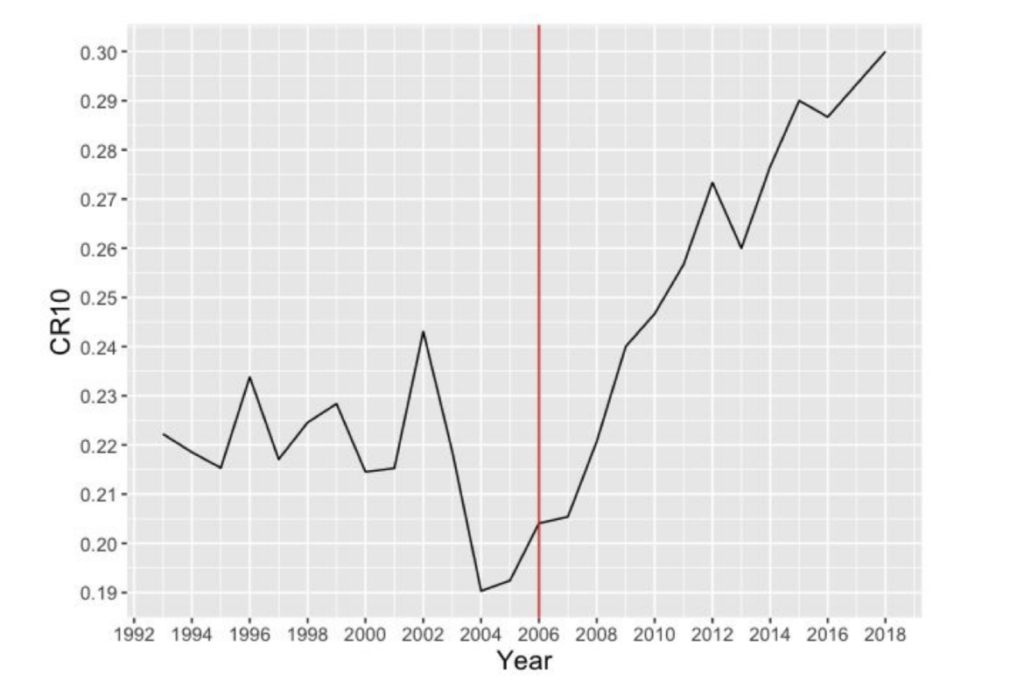

Brian’s work also uncovered another really interesting finding. When the NBA instituted a rule requiring players to attend at least one-year of college before being drafted (i.e. they couldn’t be drafted out of high school), the degree of concentration among elite schools increased considerably (Fig. 1).

It turns out that a well-intentioned rule — encouraging students to attend school and get an education — had the unintended consequence of making the elite programs more elite. And I’m pretty sure they didn’t get much of an education that year. My understanding is that the NBA is going to change this rule upon further consideration.

Finally, Brian’s paper is extremely interesting because he raises a really interesting challenge with respect to these questions. One of the concerns that hovers over this work is always: well, better programs produce recruit better athletes and train them better and that’s why they are more represented at the top levels of the sport. The same holds for academic publishing. Of course academics from elite schools get published more often in elite journals — they’re better!

If you’re like me, you’re probably pretty suspicious of these meritocracy arguments. The concentrations, at least in academia, are so high, and the benchmarks of “better” are so vague, especially in the humanities, that “excellence” seems a pretty unfounded way to justify their existence.

Nevertheless, how could we demonstrate that there is no qualitative difference in scholarship produced by academics at different institutions? For basketball, Brian turned to a metric called VORP. While I won’t go into details here, VORP offers one way of trying to assess the quality of a player. He then used it to see if players from top schools had predictably higher VORP than others.

While overall the answer is yes, for top players the quality of the school (measured in yearly draft picks) had no correlation with that player’s subsequent performance. In other words, it doesn’t seem to matter where great players go to school. They can come from anywhere. Conditioning only on elite schools would miss a bunch of great players.

We don’t have VORP for academic publishing. I’m not sure at this point how we could measure it. But the NBA case study should provide a cautionary tale in believing tales about the predictive value of “better” schools, either on the playing field or in print.