Why are Jane Austen’s novels so popular? Her characters are introverts.

As part of the work on characterization in the novel that we’ve been doing recently in the lab, I’ve come across an interesting aspect of the classic nineteenth-century novel. It turns out that female main characters are far more cogitative and perceptive than their male counterparts. However, this appears only to be true for female novelists. When men write about women, their female heroines are no more cogitative than their male ones. But when women write about women, these characters look significantly more introverted than social. Given this, we can say that one of the unique contributions that women writers make in the novel’s rise in the nineteenth century is the development of uniquely introverted characters.

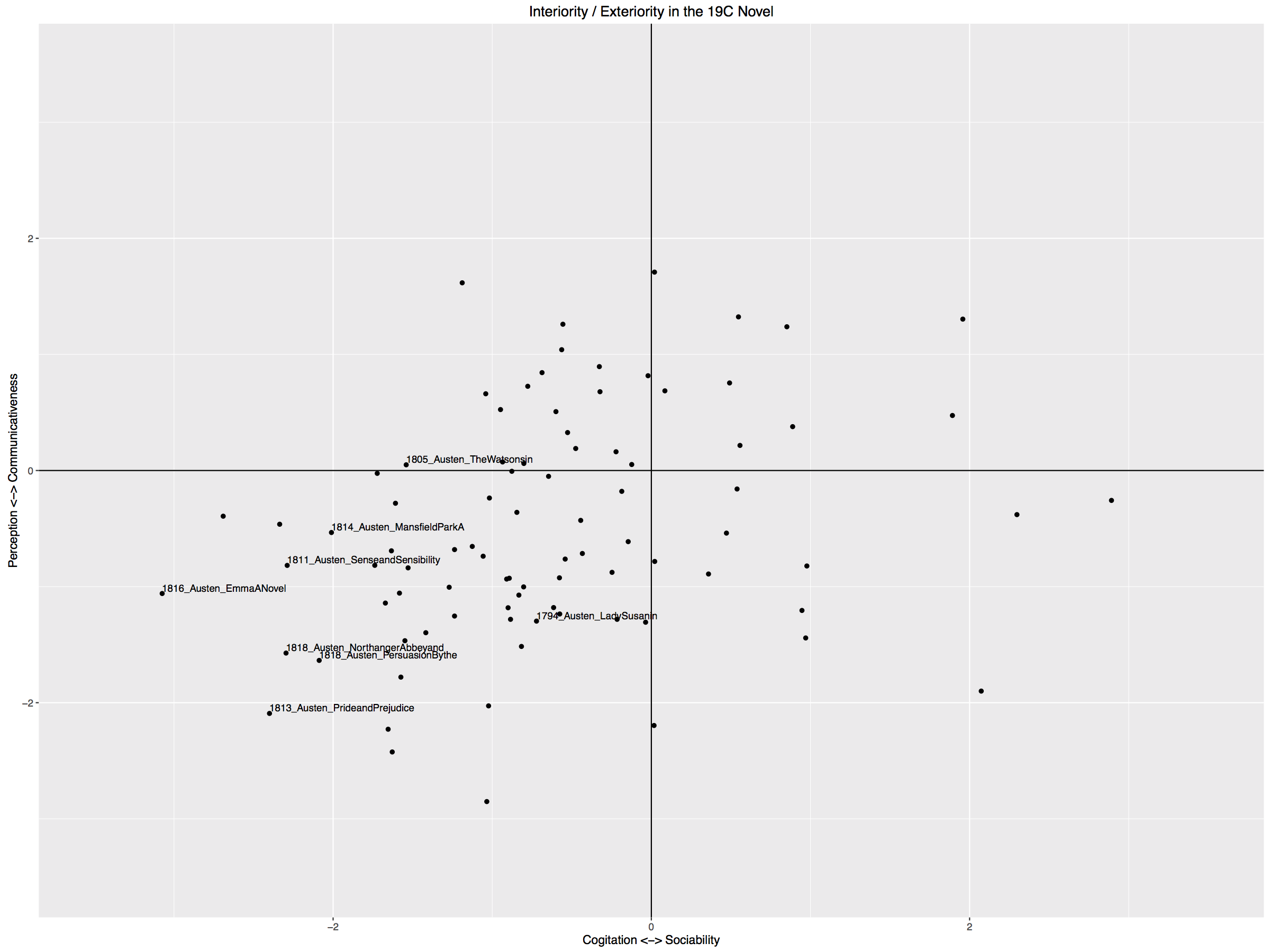

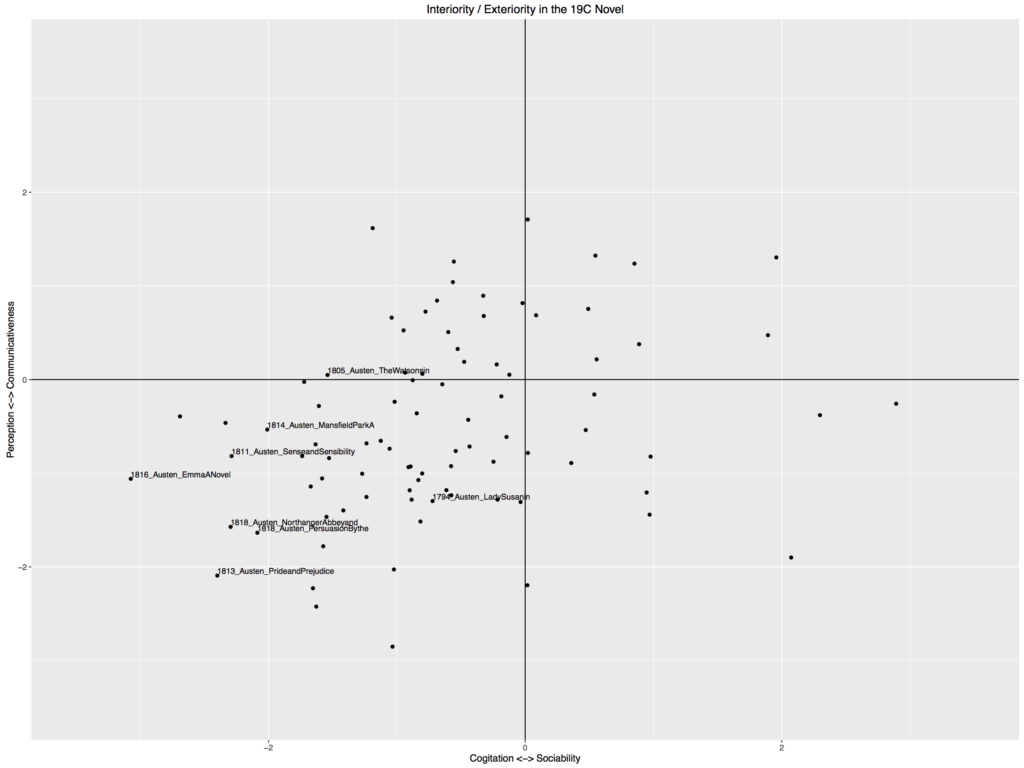

And perhaps not surprisingly for the Jane-ites out there, it turns out that Jane Austen is one of the strongest and most consistent examples of this trend (see the graph below). If we plot Austen’s novels along with other women novelists from the nineteenth century on a sliding scale of sociability v. interiority, we see not only how women tend to cluster more towards the lower-left introverts’ quadrant, but also how almost all of Austen’s novels comfortably occupy this position. What this means is that her protagonists tend to spend considerably more time thinking or observing than talking or interacting with others.

What’s interesting about this finding is the way it opens up some new questions. Is the more cogitative bias of female main characters in female novels a sign of something positive — a greater sense of inner-depth — or is it a sign of the ways women were cut-off from a variety of social actions in real life that women writers wanted to capture? As Matthew Jockers has shown, women tend to be associated with more passive-seeming verbs in the nineteenth century overall. But could this passivity in fact be a virtue, a way of imagining new modes of being in novels? It will take more work of looking into these novels to figure that out. I’m sure Austen experts and amateurs alike would have some interesting insights here.

How are we modelling our ideas? There are a few steps that I’ll walk you through. First, we run David Bamman’s bookNLP to identify characters and their aliases throughout our collection of roughly 600 novels. This captures proper names and pronouns and tries to link them together around unique individuals. We then run the Stanford dependency parser to identify words associated with these characters. Focusing on just the main characters in novels, we then look at 27 different features that capture a variety of aspects about character’s roles (how homogenous they are with other characters, how central they are relative to other characters, the types of behaviour they most often engage in, how much agency they have, etc). For this particular study we looked at just 4, which are defined in the following way:

- Sociability = The percentage of times the main character appears in the same sentence as another character.

- Communicativeness = The percentage of words associated with the main character that have to do with dialogue (said, replied, etc).

- Cogitation = Vocabulary associated with thinking, drawn from LIWC.

- Perception = Vocabulary associated with sense perception that we put together in our lab.

In order to plot the graph, I normalized the values of these four features across all of the novels in our collection according to their standard deviation from the feature’s mean. I then subtracted the associated features from one another (so sociability – cogitation and communicativeness – perception). The resulting value represent’s the character’s orientation towards interacting with others versus thinking and perceiving. The further in the lower left you are the more you tend to think and feel, while up and right means you talk and do things with/to others. This is how I’m defining introversion and extraversion here.